|

Download Adobe Reader

Resize font: Resize font:

Sarafem

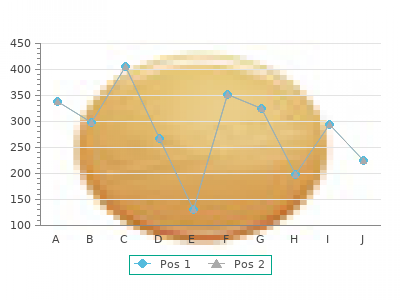

By P. Lisk. Mississippi Valley State University. 2018. Nutrition and M etabolism in Acute Renal Failure 18 cheap 20mg sarafem with visa. The extent of protein catabolism can be assessed by calculating the urea nitro- gen appearance rate (UN A) discount 10 mg sarafem with visa, because virtually all nitrogen arising Urea nitrogen appearance (UNA) (g/d) from am ino acids liberated during protein degradation is converted Urinary urea nitrogen (UUN) excretion to urea. Besides urea in urine (UUN ), nitrogen losses in other body fluids (eg, gastrointestinal, choledochal) m ust be added to any Change in urea nitrogen pool change in the urea pool. W ith known nitrogen (BW 2 BW1) BUN2/100 intake from the parenteral or enteral nutrition, nitrogen balance If there are substantial gastrointestinal losses, add urea nitrogen in secretions: can be estim ated from the UN A calculation. In the polyuric recovery phase in patients with sepsis-induced ARF, a nitrogen intake of 15 g/day (averaging an amino acid intake of 1. Several recent studies have tried to evaluate protein and am ino acid requirem ents of critically ill patients with ARF. Kierdorf and associates found that, in these hypercatabolic patients receiving continuous hem ofiltration therapy, the provision of am ino acids 1. Am ino acid and protein requirem ents of patients with acute renal Chim a and coworkers m easured a m ean PCR of 1. The optim al intake of protein or am ino acids is weight per day in 19 critically ill ARF patients and concluded that affected m ore by the nature of the underlying cause of ARF and protein needs in these patients range between 1. Sim ilarly, M arcias and coworkers have obtained a protein than by kidney dysfunction per se. Unfortunately, only a few stud- catabolic rate (PCR) of 1. In nonhypercatabolic patients, during the polyuric phase of ARF Sim ilar conclusions were drawn by Ikitzler in evaluating ARF protein intake of 0. The factors contributing to insulin resistance are m ore m ajor cause of elevated blood glucose concentrations is insulin or less identical to those involved in the stim ulation of protein resistance. Results from experim ental anim als sug- insulin-stim ulated glucose uptake by skeletal m uscle is decreased by gest a com m on defect in protein and glucose m etabolism : tyrosine 50 % , A, and m uscular glycogen synthesis is im paired, B. H owever, release from m uscle (as a m easure of protein catabolism ) is closely insulin concentrations that cause half-m axim al stim ulation of glu- correlated with the ratio of lactate release to glucose uptake. A second feature of glucose metabolism (and at the same time the dominating mechanism of accelerated pro- tein breakdown) in ARF is accelerated hepatic gluconeogenesis, main- ly from conversion of amino acids released during protein catabolism. Hepatic extraction of amino acids, their conversion to glucose, and urea production are all increased in ARF (see Fig. In healthy subjects, but also in patients with chronic renal failure, hepatic gluconeogenesis from amino acids is readily and completely suppressed by exogenous glucose infusion. In contrast, in ARF hepat- ic glucose formation can only be decreased, but not halted, by sub- strate supply. As can be seen from this experimental study, even dur- ing glucose infusion there is persistent gluconeogenesis from amino acids in acutely uremic dogs (•) as compared with controls dogs (o) whose livers switch from glucose release to glucose uptake. These findings have important implications for nutrition support for patients with ARF: 1) It is impossible to achieve positive nitrogen balance; 2) Protein catabolism cannot be suppressed by providing conventional nutritional substrates alone. Thus, for future advances alternative means must be found to effectively suppress protein catab- olism and preserve lean body mass. Profound alterations of lipid metabolism occur in patients with ARF. The triglyceride con- tent of plasma lipoproteins, especially very low-density (VLDL) and low-density ones (LDL) is increased, while total cholesterol and in particular high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol are decreased [33,34]. The major cause of lipid abnormalities in ARF is impair- ment of lipolysis. The activities of both lipolytic systems, peripheral lipoprotein lipase and hepatic triglyceride lipase are decreased in patients with ARF to less than 50% of normal. M aximal postheparin lipolytic activity (PHLA), hepatic triglyceride lipase (HTGL), and peripheral lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in 10 controls (open bars) and eight subjects with ARF (black bars). H owever, in contrast to this im pairm ent of lipolysis, oxidation of fatty acids is not affected by ARF. During infusion of labeled long-chain fatty acids, carbon dioxide production from lipid was com parable between healthy subjects and patients with ARF. Fat particles of artificial fat em ulsions for parenteral nutrition are degraded as endogenous very low-den- sity lipoprotein is. Thus, the nutritional consequence of the im paired lipolysis in ARF is delayed elim ination of intravenously infused lipid em ulsions [33, 34]. The increase in plasm a triglyc- erides during infusion of a lipid em ulsion is doubled in patients with ARF (N =7) as com pared with healthy subjects (N =6). The clearance of fat em ulsions is reduced by m ore than 50% in ARF. The im pairm ent of lipolysis in ARF cannot be bypassed by using m edium -chain triglycerides (M CT); the elim ination of fat em ul- sions containing long chain triglycerides (LCT) or M CT is equally retarded in ARF. N evertheless, the oxydation of free fatty acid released from triglycerides is not inpaired in patients with ARF.

The cross-sectional Biomedical Nijmegen Study measured eGFR (MDRD) in apparently healthy men and women (N=3732) and in men and women with comorbid conditions (N=2365) buy 10 mg sarafem with mastercard. Limitations of this study included: q a questionnaire generic 10 mg sarafem otc, rather than a clinical examination, was used to assess the health of participants q GFR was estimated with the MDRD equation and creatinine was measured only once q the GFR decline was inferred from cross-sectional data, rather than from a longitudinal follow-up. The younger and older healthy subjects were matched for body weight. This study was limited by the small sample size and it did not address rate of GFR decline. In the first study,166 the decline in creatinine clearance with increasing age was assessed in healthy males (N=548). In a follow-up study,158 the decline in creatinine clearance over time in healthy males (N=254) was compared with creatinine clearance decline in men with renal/urinary tract disease (N=118) or 74 6 Defining progression of CKD with hypertensive/oedematous disorders (N = 74). The effect of increasing blood pressure on creatinine clearance was also examined. An observational study (N=10,184, mean age 76 years, 2 years follow-up) examined GFR decline over time in older (>66 years old) males and females stratified by GFR. The decline in GFR in diabetics was compared with non-diabetics. Regression analysis of GFR normalised to body surface area was significant for age (p<0. After age 60, creatinine clearance declined steeply. This data suggests that macroalbuminuria is a better predictor of GFR decline than low baseline GFR. Renal function decreased more rapidly as mean arterial pressure (MAP) increased. Mean GFR was NS different between older healthy and older hypertensive people. Few participants in this older cohort experienced a rapid progression of CKD (decline in GFR >15 ml/min/1. Mean GFR (inulin clearance) was significantly lower in older people with heart failure (92 ml/min/1. The longitudinal studies contained mixed populations in that not all participants were followed up for the full duration of the study. The lower kidney function described in one study of older people may be due to unrecognised kidney disease. Nevertheless it was recommended that the interpretation of GFR measurements should not normally be affected by the age of the person and that a low value should prompt the same response regardless of age. The GDG agreed that a decline in GFR of more than 2 ml/min/1. The GDG recommended that, when interpreting the rate of decline of eGFR, it was also necessary to consider the baseline level of kidney function and the likelihood that kidney function would reach a level where renal replacement therapy would be needed if the rate of decline was maintained. When assessing the rate of decline in eGFR, the GDG agreed that a minimum of 3 measurements in not less than 90 days was required (depending on the initial level of eGFR). If a large and unexplained fall in GFR was observed, more frequent monitoring would be needed. Changes in GFR must be interpreted in light of the evidence on biological and assay variability in serum creatinine measurements, which is estimated at 5%. A calculation based on this would suggest that a decline in eGFR of 10 ml/min/1. However, given that a decline in eGFR of more than 2 ml/min/1. The list of possible factors associated with progression does not consider how differences in access to healthcare and poverty may influence the initiation and progression of CKD. Specifically, neither early life influences governing foetal development and low birth weight nor childhood factors contributing to the emergence of hypertension and diabetes are considered here. In those that do progress, the subsequent mortality and morbidity risks rise exponentially, as do the associated healthcare costs. A reduced GFR is also associated with a wide range of complications such as hypertension, anaemia, renal bone disease, malnutrition, neuropathy and reduced quality of life. It is therefore important to clarify exactly what factors are associated with CKD progression, and which are remediable or potentially modifiable, in order to intervene at the earliest possible stage and improve the associated adverse outcomes. The literature was reviewed to examine additional promoters of renal disease progression: cardiovascular disease, acute kidney injury, obesity, smoking, urinary tract obstruction, ethnicity, and chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). There were no studies examining acute kidney injury or urinary tract obstruction on progression of CKD. In a pooled analysis of the ARIC Study and Cardiovascular Health Studies (CHS), kidney function decline (serum creatinine increase ≥0. A diabetic cohort of smokers (N=44, mean age 47 years, 86% had baseline proteinuria >0.

He had accepted that staff with greater ambition would gain more promotion sarafem 20 mg on-line. He shared an office with a married woman discount sarafem 10mg with amex, Penny Hope, who was a few years and one public-service level senior to him. He had a good knowledge of his area of work; he had learned what he needed to know about computers and felt secure in his position. One day Penny came back after lunch and found that John had moved his desk. He had moved his so that it was now against a wall adjacent to hers. When she asked John about it, he was evasive and said that it was “for the best”. Penny thought this was an unsightly and unnecessary mess, but again, she said nothing. She had recently found John to be tense and serious. She soon found him to be quick to take offence and prepared to argue over minor details. Last modified: November, 2015 12 Any discussion they had about the taxation of multinational companies ended in an argument – even when Penny was careful. Penny noticed that John was not working effectively. He began spending too much time checking his calculations, and was not getting through the required volume of work. Then he began doing his calculations with a pencil and paper. Because their tasks were inter- related, his slowness was reducing her output. She hinted, she would be prepared to take over some of his tasks. Partly out of concern for him, and partly out of concern for herself, Penny went to her superior. She was surprised, saddened and relieved to hear that others had noticed a change over the last year. As long as anyone could remember, John had bought his lunch at a sandwich shop and eaten it with the same group of men in the staff room. In the summer he had talked about cricket, and in the winter, football. During both seasons, he had tried to recruit the sons of all new employees for the Surf Club. Now, he brought his lunch from home and ate it alone in a park. People in other sections had begun to complain about him. In the past, when he detected inaccuracies or oversights in the work which came to him he had done the usual thing, called the authors, teased them and passed on. But, then, uncharacteristically he took one of these errors to his section head; it seemed that he could not accept an honest mistake had been made. It was taken as an insult; it was an awkward situation and the section head let the matter drop. Still, John had not acted illegally, improperly or contrary to the Public Service Act, and there were no grounds to discipline him. I just asked you to come up to have a chat, to see if you Pridmore S. Last modified: November, 2015 13 like it here, and whether there is anything we can do to help you work things out,” he said, in a kindly manner. Thus commenced a union, legal and medical wrangle which lasted for two years. John contacted his Union Representative and stated he had been threatened with the sack, without warning or reason. This was believed and repeated by the Union Representative. Then John went on sick leave, his doctor claiming that he was suffering from “nervous exhaustion”, due to “industrial harassment”. After months of discussions and letters, denials that there had been harassment and agreement that there was no hard evidence, John (possibly agitated by this turmoil) made an unexpected visit to the Consumer Protection Authority. Sarafem

9 of 10 - Review by P. Lisk Votes: 107 votes Total customer reviews: 107 |

|